Geoffrey Hinton Family Tree: From Mount Everest to AI

Larry Cao

8/5/20253 min read

Geoffrey Everest Hinton’s recent Nobel Prize in Physics took many by surprise, highlighting once again his pivotal role in developing artificial intelligence. Yet how many people know the story behind his middle name, “Everest”?

It turns out that Hinton’s family background is as remarkable as his professional achievements. This may not be so surprising when we consider the importance of natural aptitude and upbringing in shaping a person’s future. Some studies have suggested that success in life can be roughly attributed half to inherited dispositions and half to environmental influences, which are often related to parental resources, social status, and an individual’s own efforts. In Hinton’s case, a longstanding family culture of intellectual curiosity and a supportive environment may have played a role alongside his personal diligence.

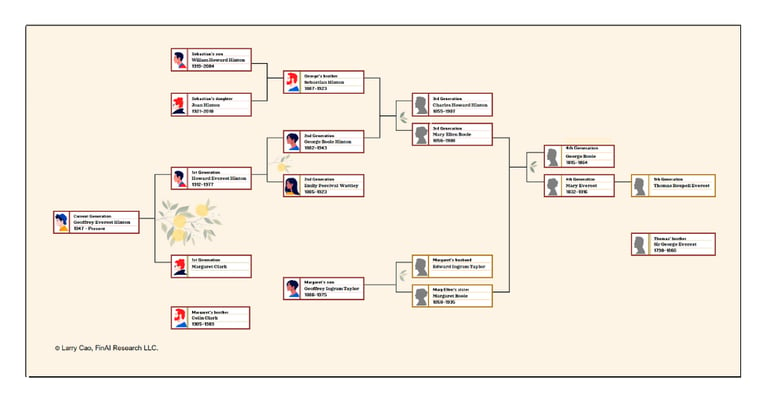

This intellectual legacy traces back to Sir George Everest (1790–1866), Surveyor-General of India, after whom Mount Everest was named. Though not known for formal academic degrees in the modern sense, Everest came from a milieu that valued exploration and scholarly interests. His niece, Mary Everest (1832–1916), carried on this tradition. She married George Boole (1815–1864), the first Professor of Mathematics at what is now University College Cork in Ireland. Boole is celebrated for developing Boolean Algebra, a groundbreaking mathematical system that underpins all modern digital logic and computing—a fitting ancestral link to Hinton’s work in AI.

From George Boole and Mary Everest’s marriage came children raised in an environment that prized learning. One daughter, Mary Ellen Boole (1856–1908), married Charles Howard Hinton (1853–1907), who studied at Oxford and later taught at Princeton. Charles Howard Hinton explored higher dimensions and the “tesseract,” anticipating some of the conceptual complexities modern computer scientists confront in abstract, multi-layered neural networks.

Mary Ellen and Charles Howard Hinton’s children ventured into diverse fields. George Boole Hinton (1882–1943), Geoffrey Hinton’s grandfather, worked as a mining engineer. Sebastian Lionel Hinton (1887–1948), who earned degrees from Yale (BA) and Harvard Law School (JD), invented the jungle gym, stimulating the physical and mental development of generations of children. His own children took varied paths: William Howard Hinton (1919–2004, Harvard alumnus) wrote influential works on agricultural development, and Joan Hinton (1921–2010, University of Wisconsin–Madison) engaged in physics research, even working briefly on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos.

Another daughter of George Boole and Mary Everest’s, Margaret Boole, married Edward Ingram Taylor, eventually leading to the birth of Geoffrey Ingram Taylor (1886–1975). Taylor, who studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, became a pioneering figure in fluid dynamics, applying rigorous mathematics to understand complex physical phenomena. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1919.

Generations of Innovative Thinkers. Lines indicate Hinton’s direct ancestors.

Howard Everest Hinton (1912–1977), George Boole Hinton’s son and Geoffrey Hinton’s father, earned his BA at UC Berkeley and PhD at Cambridge, later becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society and a Professor at the University of Bristol. He introduced a new recognized stage in insect metamorphosis, broadening scientific understanding in entomology. He also supported the then-emerging acceptance of continental drift.

Howard’s wife, Margaret Clark, was the sister of Colin Clark (1905–1989), an Oxford-educated economist whose innovations influenced how we measure national economies. Colin Clark introduced and refined the concept of Gross National Product (GNP), and through his landmark studies—such as National Income and Outlay (1937) and The Conditions of Economic Progress (1940)—he helped establish the quantitative backbone of modern economic policy. Clark worked at institutions including Oxford and the University of Queensland and served as an advisor in various countries. His approach attracted the respect of John Maynard Keynes, who described him as “almost the only economic statistician I have met who seems to me quite first-class.” This was a ringing endorsement in a field where measurement methods significantly impact public policy and economic understanding.

Fast forward to Geoffrey Everest Hinton (1947– ), who studied Experimental Psychology at King’s College, Cambridge, and earned his PhD in Artificial Intelligence at the University of Edinburgh. He benefited not only from his own determination and creativity but also from growing up in a family where learning and questioning were second nature. If there was an inheritance at play, it was not only in natural dispositions but also in a nurturing environment rich with examples of intellectual effort and curiosity. It’s a background that helped set the stage for his extraordinary accomplishments in shaping the technology that defines our era.

So the next time you hear of Geoffrey Everest Hinton’s achievements, remember: while personal perseverance and innovative thinking are at the heart of success, the environment and intellectual traditions we inherit from previous generations also matter. In Hinton’s case, a family history of academic inquiry, creative problem-solving, and wide-ranging intellectual pursuits helped build the foundation on which he continues to stand today.

This article was originally published on Larry’s Substack, larrycao.substack.com, on December 16, 2023, and has been repurposed for broader access here.